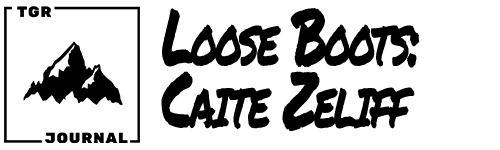

Caite Zeliff, about skiing, passion, obsession and mental health

Loose Boots: Caite Zeliff

Story by Taylor FryA lot of athletes talk about their 'mental game.' But not so many of them talk about their mental health, and few athletes, let alone people, talk about it as candidly as Caite Zeliff. TGR Athlete, two-time Queen of Corbet's and all-around badass Caite Zeliff sits down with our own Taylor Fry to chat about her journey to where she is now and how mental health and skiing are intertwined.

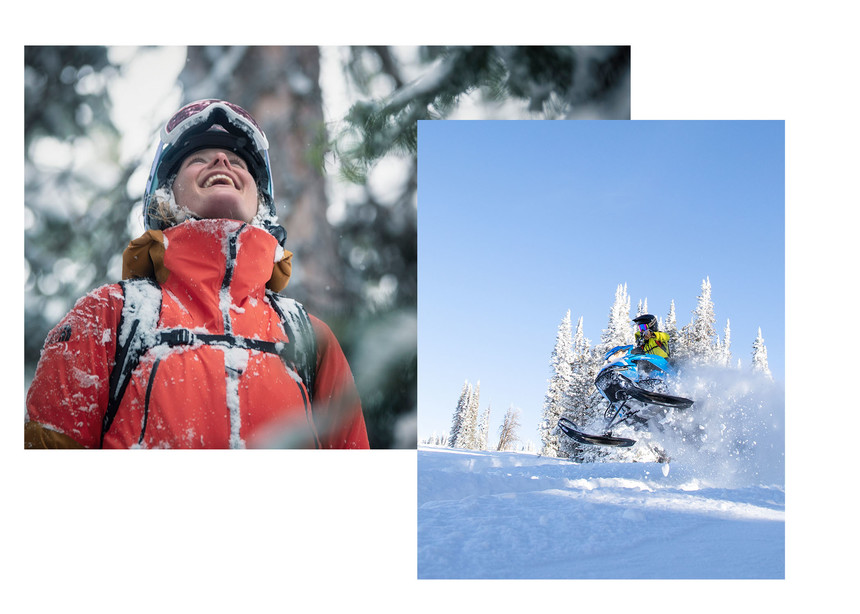

Caite doing what she does best. Chris Figenshau photo.

Kick your feet up, wiggle those toes and stay awhile - we’re about to get comfortable. In this entry of Loose Boots, we’re chatting with TGR athlete, friend and roommate of mine, Caite Zeliff, about skiing, passion, obsession and mental health. Who’s behind all these hucking, chucking, manicured clips of the dream? How much is too much when you’re chasing after the dream? What makes an athlete an athlete? At their core, they may not be too different from yourselves.

If you’re lucky enough to know Caite, you’re lucky enough. As a rarity that navigates through life driven by a passion for her craft, her journey is worth taking notes from, as she is also learning from it every day. Since Zeliff has broken into her profession, she’s noticed many similarities among athletes of her craft that seem to balance on varying levels of extremity. In this story, with the help of Zeliff and local Teton County Sports Psychologist Christina Heilman, we will explore where the lines are drawn (if there are any) between hobbies, career, obsession, as well as flexing muscles more related to skiing than you may think.

Let’s get to know Christina Heilman. She’s your new favorite sports psychologist and keeper of all wisdom. Hint: this may feel like a therapy session. You can thank her later..

The second I connected with Dr. Heilman, she immediately made my fast-paced, overwhelmed brain train come to a screeching stop. I could imagine her bubbly persona as her calm, lighthearted voice trickled through the phone. Let’s get to know her.

Per her training, Dr. Heilman is a sports psychologist, or as she prefers, a Mindset Coach. Zeliff put me in touch with her to have a discussion based around the importance of mental health in general, but with a specific focus towards athletes at all levels. “There are different layers to it,” she says, “both me and a therapist are trained, but in different ways. I am trained as an athletic trainer, a strength coach, and have a holistic view on the crossover between Clinical Therapy and what I do. Readers note: Dr. Heilman is not a trained, licensed therapist. She is trained through the Kinesiology Department / Sports realm in Educational Sports Psychology. For example, if you’re bipolar, she can help, but will not diagnose.

As a kid growing up in South Dakota, Heilman found sports as her avenue to live well in aspects of the mind, body and heart. When she was injured as a teenager, she was stripped of what she loved the most, which led to an identity crisis and tumbled into a depression.

That was when she first realized the connection between the body and the mind. Her experience during her injury inspired her to pursue her passion: focusing on the mind body connection: How does it work, and, like any good athlete, how do we train it? The brain is a muscle, no?

“I can train these athletes, but really, there’s this mental and emotional side to it.” Throughout our conversation, Heilman refers to her patients through the metaphorical embodiment of a table: “I tell my patients that they’re a table, and all these things that they’re focusing on are individual legs. If you just focus on the physical leg, and ignore the others, then the one you’ve focused on the most gets injured, you won’t have any other legs to stand on.”

During her injury, Heilman realized she “didn’t have any coping skills to deal with the repercussions. Which led her to wonder, “Why aren’t athletes trained to have this skill-set?” Which is a fair question to pose: Why not train the mind of an athlete as intensely as one trains the body?

“I was fascinated with the side of the mental game,” Heilman tells me over the phone. “When I was injured, I thought, how do I build confidence to return to play? Can we build a strong boat before we go out to sea? Can we be proactive about helping youth before they get hurt? How can we give these athletes the skills to deal with stress and anxiety?” While she was getting her degree at the University of Utah, her research in this subject ended up winning the dissertation of the year award, which is a Gold Medal in Academia. “Not as big as a gold medal in the Olympics,” she laughs, “but pretty dang close.” She then moved out to Driggs, Idaho, ski patrolled at Targhee, went back to school to get her PhD, and started the business she has today.

Dr. Heilman started working with all-mountain athletes, which snowballed into Black Diamond reaching out to ask her to work with their climbers and skiers. “It never crossed my mind,” she said, “that something I was teaching was something that no one else was really doing or paying much attention to.”

Her circle of patients now is an established cluster of big mountain skiers and climbers. “It’s about performance some, but really, it’s life coaching. Peak performance comes from peak wellness. Patients will come to me and say they don’t know what’s going on with their brains, but they know that something is getting in their way, and they want help trying to get rid of it. I believe everyone I see has the answers inside them, they just need help getting it out.”

Keegan Rice photo.

It wasn’t by chance that Zeliff and Dr. Heilman connected. Like many others, last year was an obstacle for Zeliff. “It rocked me in a lot of ways.” She tells me this as I sit on a thin carpet on the floor of her bedroom. “All of the sudden,” she says, “I was like, ‘This is my dream. Are you f*cking kidding me?’”

Realizing that your dreams are now reality would be a lot of pressure for anyone, especially in a sport where there are a lot of eyes on you. Expectations grow, and focusing on the joy you originally got from the sport begins to shift. Heilman tells me, “When you add the sponsors, the money, the recognition, those are extrinsic motivators. That comes from outside of you. Extrinsic motivators undermine those intrinsic reasons you started something to begin with. When you lose the fun and joy in learning, the reason you started something in the first place, and the hobby you love turns into a job, it can easily suck the life out of you.”

Which, Zeliff will admit, is a darkness that she’s danced with. In high school, she was the opposite of where she has worked her mindset to be at now.

Caite: “I was really hard on myself, ultimately to the point of causing depression. I was my worst enemy all the time.”

Taylor: How so?

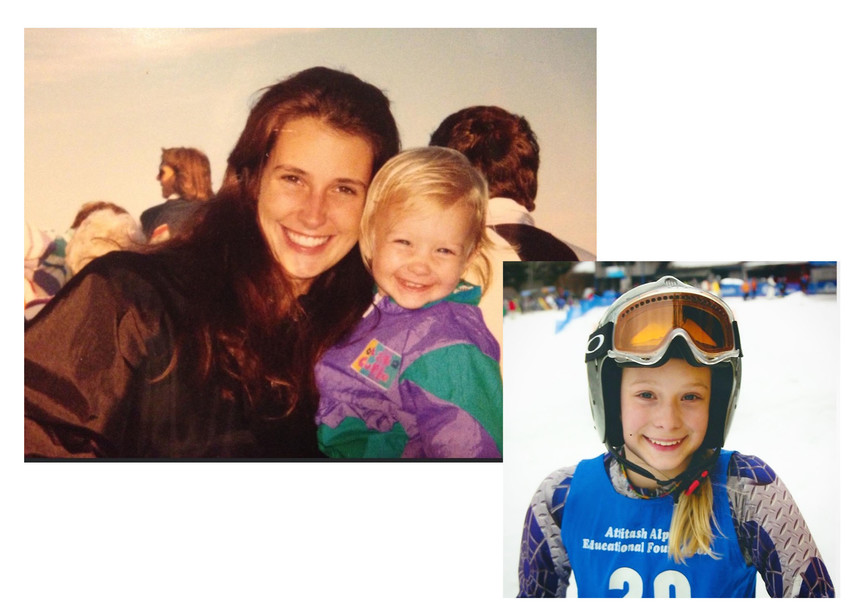

Caite: During high school in the off season, I had to get super strong and fit for my other Varsity sport. I had to get good grades because ultimately, my goal was to make the US Ski team, or I wanted to get on the US Ski team from college. Most likely, that boils down to going to an Ivy League school. Staying up late and partying too much also shockingly doesn’t help achieve those things.

The reality is, I was abused as a child by a stepmother and then my dad made a choice to be gone. A court didn't remove him. He chose to be absent, even while being fifteen miles down the street. This is me dissecting with therapists, and I think that made me super hard on myself. I think I wanted to prove to him that I was worthy, and was constantly asking myself why he didn’t want to be around me. I was really being raised by my mom, who was also super f*cking broke. She was doing a lot to keep me at private school. I had a full ride, but that doesn’t cover everything. I wanted to prove to her, too, that I was taking advantage and it was going to a good cause.

She didn’t put pressure on me, but I put so much pressure on me. It was weird during ski racing because she would say, ‘Just quit, it’s not making you happy.’ But that was the only thing I was good at. I just wanted to prove something to everyone.

Taylor: How do you move through that? Realizing you were putting too much pressure on yourself?

Caite: When I got the call to try out for the US Ski team was the moment I realized you could manifest shit. I was driving home from school in a Saab Station Wagon Turbo. I can picture the corner and the downhill perfectly. I was thinking about how I wanted to be on the US Ski team so bad… and suddenly I had an overwhelming feeling of gratitude, thinking about being on the US Ski team, listening to music and just vibing. I get home and my mom goes, “You have a call,” and it was my ski coach. I pick up and he goes, “Dude. Zeliff. You got chosen. You’re going to the National Team tryout camp,” and I was like, “Hang on. Mom, I made this happen.” My grandmother and mom introduced ‘The Secret’ to me, and since then, I always worked on manifestation.

I knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to be on the US Ski team and travel the world. I wanted to be an effing Rock Star in Europe. That’s what a ski racer is. That’s when I realized being there, living my dream, was a possibility.

Fast forward to the National Team tryout camp. I’m skiing faster than I should be. I’m beating all these girls and kicking ass. Then we went into the gym, and I got nervous, I didn’t know what to do there. All the other girls were well-trained athletes, and everyone saw me crack under pressure.

Left: Zeliff enjoying winter in the Tetons. Nic Alegre photo. Right: Zeliff gets after it on a sled too. Keegan Rice photo.

I remember there was this back bowl at Mammoth, where the tryout was. I was a speed skier, mind you, and me and all the other girls were on our Super G Skis. The coaches look at us and look down at the bowl, over this huge mogul field and say, “Show us what you got,” and I straight lined it. I ended up going over this mogul so big, and going out of the bowl and dropping into a terrain park onto a roller and thought I broke my back. The coaches came down and said, “Well you can take a girl out of the East but can’t take the East out of the girl,” and that f*cked with me. Later, they basically told me I wasn’t mature enough, and I fully lost my shit and had a mental breakdown Junior year of high school. It was a breaking point.

That was the darkest time I hope to ever experience. Mental hospitals, violence, and medication were involved and it was gnarly. I was so depressed, the only time I was happy was when I was driving my car 80 mph and skiing 100 mph. I would drink like crazy, and was not a good version of myself and I didn’t know why. That’s when I started seeking out my dad, because depression ran on his side of the family and he was an adrenaline junky. I was just searching for some sort of understanding.

I think it took me two years to recover from that. I was living with the Headmaster at my boarding school (because I got in trouble) but I was also on suicide watch there. It was not what I wanted to do or be. That was senior year, and around the same time as all this, we had our Senior Projects. That’s when I started doing research on the mind of extreme athletes. I interviewed a paraglider, National Geographic athletes and the Davenport family.

Taylor: Do you think talking to other athletes helped you get better at understanding yourself?

Caite: Definitely. When I began talking to other athletes, I started to understand that high functioning people sometimes struggle with anxiety and depression. I was able to shift my mindset. Instead of being like, “I’ve got this thing,” it became, “I have this thing because I have other gifts.” Medication probably helped in some ways too. I’m not saying it’s the answer, but it took the edge off. Also, just growing up. I always had this focus on skiing, and a lot of my lessons have come from that. The reality of being an internationally-ranked ski racer is that you’re traveling a lot by yourself. You’re young, you’re not with your parents. So slowly, I was growing up through skiing. There wasn’t anything else that helped that. At the time, I hated therapy. It didn’t help me. So I guess it was time and growing up, and I was just lucky enough that I never got off track - because I was that obsessed.

After I graduated High School I took a post-grad year and that’s when I transitioned out of the ski racing world. I skied for one year in college at University of New Hampshire, but blew my knee out and then moved out to Jackson. But even then, which was five years ago, that shift away from what I knew to be my identity as a Ski Racer wasn’t over. I don’t think it’s ever over. F*ck yeah I want to prove myself. I haven’t grown out of that. I think now it’s just less to other people. I’ve grown into understanding that being hard on yourself doesn’t help. And the power of positivity is huge. It’s true. Have you seen this experiment on Plants? I think it’s mostly the understanding that I want this so fucking bad, and if I didn’t deal with my mental health, it’s something that could and would stand in my way, so why let it? The other option is much better.

Taylor: I feel like there are people that lose themselves after what you experienced. After dedicating your life to something and having your dream seemingly crushed… some people don’t make the team and they’re done. It says a lot how you could take that motivation and turn it into something else.

Caite: Ultimately, I knew I didn’t want the US Ski team. I was seeing the inside world and felt that it wasn’t for me. The transition away from what I thought I wanted into something that was actually what I wanted probably helped. I mean, no offense, ski racing is cool… but big mountain skiing… way effing cooler.

Present day, Caite will be the first to tell you that all around, she’s in a different place. She’s worked into a shift in her mindset with some kind of Jedi focus that I’ve never really seen in anyone else. The kind of hungry drive fueled by passion that is other worldly. However, and you may already be thinking this, does that streamlined focus ever come at a cost?

Upon my musings with Dr. Heilman, we discussed a state of mind called the Flow State.The Flow State, which is used by many popular positivity psychologists, describes a feeling that “When and where, under the right conditions, you become fully immersed in whatever you are doing,” as positive psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihaly explained in his 2004 TED Talk: “There’s this focus that, once it becomes intense, leads to a sense of ecstasy, a sense of clarity: you know exactly what you want to do from one moment to the other; you get immediate feedback.”

Could being in the Flow State at a consistent, high functioning level mask itself as an unhealthy obsession? Is it something that can be interpreted as giving you tunnel vision? As Dr. Heilman reminded me, there is always dark with light. With our conversation narrowing in on this state of mind, she had nothing but wisdom to share.

Taylor: Can you speak a little bit to Flow State? Even though it’s regarded as a positive state of mind, could the argument be made that there is a dark side of it, too?

Heilman: When there’s light there is also dark, you can’t have one without the other. For every strength, there’s a weakness. If you have a lot of grit, you have passion and persistence to reach your goals. These are people that are ‘successful,’ but on the other side, they burn out.

There is an equal and opposite balance to that. You keep going and going and then you reach a point where you’re like, “I am so burned out,” and you need to implement healthy boundaries. If we’re talking about achieving a goal – for example, skiing something big or training for a half marathon all season, you experience the post-send or post-race blues. When we’re in a flow state and achieving goals, we get a massive influx of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, which are feel-good hormones that send you flying. This pushes you toward and through your goal. But when it’s done, you’re not getting those neuro chemicals anymore. The post-send race blues happen because your body has been so used to getting feel-good hormones, and when you lose that, there is opportunity for depression, and or, a lot of darkness.

Taylor: How do you think you avoid that?

Heilman: The thing with people is that we keep chasing that next thing. People want to be in flow because it makes you happy. Or, maybe it becomes consumerism, like anything else? Does it become, “I need to get the car, the job, and then I’ll be the best, or I’ll be happy.” If you’re going and pushing the limits, physically and mentally, is it for yourself, or is it a mental game? If the root of that is a thought like, “I’m not enough,” the root of that is “I’m not enough so I need more to keep filling my cup up.”

That thought of thinking you’re not enough is fear based, which is deeply rooted, and you end up being motivated by your fears. Everyone has been there. I had a baby six years ago and was exercising excessively because I had a fear of getting fat. I didn’t know it was a fear until I brought it to my awareness. Once I did that, I wanted to exercise because it was something I loved, and that I wanted to go because I wanted to be good in the mountains, doing what I love.

Chatting about this rather unseen side of Flow State seemed to resonate to what Zeliff has experienced as well:

Taylor: Can you talk about Flow State? Have you ever experienced it so deeply, that it’s put you in danger in some way or another? What’re the consequences of that?

Caite: When we were filming for Make Believe on Cave Air day, I was in a flow state that I could control, like lucid dreaming. I had a bunch of female rap that I was listening to which calmed me down, and Jim Ryan and I were vibing and the world was moving slower… I was drunk on that. I was going big all day, and then went over to Gothic. By then, there’s no light, it’s been hot all day, the snow is crusted up and I can’t see shit. I know these things are bad because I’m a skier, but I ignored them. I tell Jim I like it. He’s thinking, you’ve done plenty - but he knows I’m hungry. I look at him and ask if he thinks this is a good idea and he said ‘That’s up to you.’ So I say I’m going for it. I couldn’t find my mouth guard, that’s strike two. It’s in my gut that I shouldn’t do it. I knew what was going to happen. Strike three. I stomp and I’m like, “Holy shit I did it.” Then… I let my guard down, got out of flow state, did some high speed tomahawks and the eighth one ended with me around a tree with my leg snapped, and came into immediate shock and adrenaline off my injury.

Taylor: How long were you out for because of that?

Caite: Eight weeks. That's when I started training again. I was back to 100% by mid June. Back on snow fully when the season started.

But at that time in March when everything was hitting the fan, I was living in what was practically a dungeon, COVID was raring, and I had this broken leg. Jim came over later that day and said he had never seen that side of me before. This reckless ambition. And right then, I thought about my depression, and that the only time I’ve been happy I realized is in that moment, before that moment or after that moment. That’s something I’ve been working on with meditation and mindfulness and being present.

Left: Zeliff crushing pow. Nic Alegre photo. Right: Zeliff after a crash.

Taylor: Is that the line? I mean, how much is too much when you’re chasing the dream? Have you ever had to put your foot down when you reach that point, or maybe the line doesn’t need to be drawn – just moved?

Caite: To me, obsession makes it so there isn’t a line and there isn’t a difference. Skiing has always consumed me. I always put myself in this box. I was a ski racer through and through. That was my identity. But when I blew my knee out, I could get away from that. Now I’m a big mountain skier, through and through. For example, learning how to paraglide this summer was because I just wanted to mess around with something and not have the expectation to be great. I had a shitty year last year. In really beautiful ways, but it was too much. I knew it was because I was slipping back into depression. If we’re talking about tables, that shit was on the ground. All I did was ski, and talk about skiing – and now, for example, all the bodywork I’m doing is just as much for my mind as it is for my body, and it wasn’t always like that. But if it wasn’t for skiing, I don’t even think I’d be doing that for myself. So it goes hand-in-hand.

Taylor: How do you manage that? If you are in a place and need to break out of it to take a breath? How do you conceptualize moving from something that is a pure driver in your life?

Caite: I realized at a certain point that obsessing over something doesn’t help you. Take a backflip for instance. If I’m doing it over and over again, I won’t get it. I need to take a step back, go ski some pow, and not for nothing, ski racing taught me all this. I wasn’t good when I was scared and intense and visualizing - I was skiing so tense. I’m not proud of it, but when I was younger, I started drinking during races because I was terrified and over it. My skiing was smooth and beautiful because I was calm and relaxed. I was in a world of Type A’s, and all I was seeing was that there was one way to the top and that was it, and I was wondering why it wasn’t working for me. But I learned that being hard on myself wasn’t helping, and now in the world of big mountain skiing, it’s pretty unwritten. There is no proper way to get there. It’s the opposite of ski racing, and it has helped me come to terms that I operate a bit differently.

Taylor: Would you say that skiing has given you the tools to deal with whatever you’re going through?

Caite: Totally. When I first started getting recognized and going on tours I was nervous and intimidated. As I started feeling more comfortable with my performance, I would lean on my achievements to give me confidence for other things. Like saying to myself, “you hucked 65 feet into Corbets. Go into that room, you’re fine.” Having that ski identity gave me that confidence which allows me to reach a headspace and say, “Dude, you’re effing capable.”

With skiing, it was the first time I felt applauded. Without it, I would’ve been the most insecure person in the world, which also comes from being in an abusive home, but this thing gave me confidence otherwise, that’s why I want people I love to find passions too. It transforms you.

Dropping into Corbet's Couloir. Carson Meyer photo.

I turned to Heilman again for her input on why focusing on the leg of your mental health is imperative for everyone, especially athletes, who may not prioritize that muscle or consider it associated with their performance.

Heilman tells it like it is. She says, “Sports are so concrete, and life is so abstract. When you’re an athlete, you have all these measurements of how you’re getting better, stronger. You obsess over the numbers, and improving makes you feel good. It releases dopamine – a chemical that makes you feel good and it’s like a laser beam instead of a bright light, and you go for it until something makes you say, “Oh, something’s not right.”

“Truly, you have to do that in a sense to get to that level of competition,” Heilman says. When talking about an athlete like Zeliff, someone that has learned from every bump in the road and pulled light from dark places, having her intensity steer her ship in the direction of her current port, it might be true.

“It’s great when you have intention,” Heilman tells me. “When you can say, ‘I know the other legs I’m not paying attention to, and that’s ok.’ When you’re aware you’re making that choice, you have the power. You need to say, I know those legs are wobbly, but I have to pay attention to this other one, and trust that those other ones will come.’”

In terms of elite athletes, she notes that they, “don’t pay attention to all the legs, they can’t really. There needs to be direct focus when perfecting your craft, but is there something a little loose about that? How do you become aware in that moment? It must take a lot to bring back your intentions, especially when you’re on a high of all this reward.”

Taylor: How do you lose the joy in something that you’ve been dreaming of, manifesting, working toward your entire life? More importantly, how do you get it back? Heilman comes in with both the answers, unsurprisingly.

Heilman: Athletes go to a certain level because they’re intrinsically motivated. I personally love to learn and be with my friends, it comes from the heart. This goes the same for athletes. But then you add the sponsors, the money, the recognition, those are extrinsic motivators. That comes from outside of you. Extrinsic motivators undermine those intrinsic reasons you started to begin with. When you lose the fun and joy in learning, when you’re thinking “Now I need to get this and do this” when it becomes, this hobby that I love turns into a job, it can easily suck the life out of you.

My main goal with professional athletes is to help them bring the joy back. When we talk about grit and burnout, it’s like, “Oh right, I forgot I got lost in those sponsorships and movies and social media posts. I forgot why it was joyful and why I was doing that.” Your brain remembers the last thing you do, so make sure you end it on a good, fun note. For climbers, get on something easy and fun. With skiing, maybe you did these hard things and you can’t ski another line, but maybe you can connect with a friend, take an easy lap, get some pow shots, laugh, look at the scenery… that’s what is ingrained in your mind to keep that motivation to keep going the next day.

That seemingly is true, too, in Zeliff’s case. There is a little dark in the light, there has to be a little push when it comes time to shove. But an ongoing question is, how do you control these things and find balance? The answer in question, especially this season, is what Zeliff is trying to embody: Come back to finding the joy.

Taylor: Why do you think burnout happened last year?

Caite: I wasn’t enjoying myself. There were parts of me that I was enjoying myself because, well, f*ck it - feels good to be doing something you want to do. This year is different. Jim Ryan (longtime friend of Zeliff, local skier, Helly Hansen athlete & part-time model) and I made a wild connection in the past week or so. Writing notes back and forth. It feels like I’m now finally able to say, I’m a pro skier. Last year I didn’t believe it. I was like, “I’m going to show them.” Now, for whatever reason, I don’t have anything to prove to anyone.

My friends have also been checking on me, and one of my idols the other day said that she hadn’t seen someone come up in skiing in a while with genuine love for the sport. It gives me a beautiful perspective because I didn’t see it like that, but now that it’s brought to my attention, I do. I believe it. For example, the other day I had the best day with my friends in the mountains. We were goofing off but also being serious. It’s the combo of being dialed and lighthearted. It’s the best version of me.

Keegan Rice photo.

Growing up to understanding herself and connecting with like-minded people has led Zeliff to be the athlete and person she is today: Grounded, present, working to seek out the joy, and still learning. One of Zeliff’s biggest sources of joy right now involves skiing (of course), and a little bit of creation.

Taylor: How did your upcoming project, Hardwired, come to fruition?

Caite: It’s fun to create with my friends. I’ve also always loved ‘Thrasher: King of the Road,’ and one day I was thinking, “How sick would it be if you took all the Volkl and Atomic athletes, shove ‘em in a van and go to ski areas and make edits.” Each week, there’s a winner or there are tasks. Some of them are funny, like how many people can you make out with (pre-COVID), or how many skateboard tricks you could do. I liked it so much because you get to know the skaters - who they actually are.

I got caught up with snowboard and skate rough film. I decided that I wanted to do a BTS thing, that has morphed with the help of Christine Reppa, Charlotte Percle, Jim Ryan, Keegan Rice and Stephen Shelesky. We’re pitching Hardwired as four episodes (Winter) and the 5th being in the Summer. Jim and I are the athletes, so it will be following Jim and I on our path, following our dreams and as mountain partners, mainly focusing on the inner moments that you don’t see.

We both have this ex-ski-racer drive and a level of devotion that’s hard to find in the ski world. I realize his level of obsession is on par with mine, and it’s sick. He keeps me in the direction of who I am: A big line fast skier. I want to do what I want to do and do it for the right reasons. Not for the fame or the followers. The other day, Jim said, “Don’t worry about backflips.” And instead, we hopped on sleds. That kind of stuff is important to do with someone that understands you at a deeper level. Stories are important, and sometimes perspectives and stories themselves are confusing. I want people to help me tell the story of what’s going on, because I’m in it and sometimes that’s a harder story to tell.

“Right now,” Zeliff tells me, “I’m in a pretty good place, but there’s nothing that’s weighing on me. In my opinion there’s nothing apparent to take care of, but I know there is.” Per Heilman’s advice, and probably Caite’s own intuition, Zeliff is taking things one day at a time, but still chasing after, and reveling in, living her dream.

Caite living the dream. Charlotte Percle photo.

Caite: There’s never been a time or a place where I’m not doing something that’s not calculated toward a goal. But now, I’m really enjoying every minute of my day, which is new for me. I wake up and I’m rested. And that energy, my energy, is attracting a lot of good things. I literally live this life, my dream - how could I possibly be mad? That was a long time coming, and don’t get me wrong, there are bad days, and there are times within the good days where I say negative things to myself, but I’m now able to catch myself and say, don’t be a f*cking loser. Even when things are amazing, and I’m saying shitty things about myself, or the scene, I can redirect it more so than I used to. That’s why I wanted to start this project. I just want to tell the story of how these people, like myself, these obsessive, passionate, driven people, athletes and artists alike, one’s that are on this drive to our dreams - we’re just hardwired differently. And that’s more than ok, it’s great.

***

To put this story in perspective, The National Institute of Mental Health states that nearly one in five adults in the USA suffer from mental illness. That is 51.5 million as of 2019. (1)

In young adults, especially athletes, the statistics are even more astonishing. Athletes for Hope report that “33 percent of all college students experience significant symptoms of depression, anxiety or other mental health conditions. Among that group, 30 percent seek help. But of college athletes with mental health conditions, only 10 percent do. Among professional athletes, data shows that up to 35 percent of elite athletes suffer from a mental health crisis which may manifest as stress, eating disorders, burnout, or depression and anxiety.” (2)

If you or anyone you know is struggling with their mental health, here are some useful resources below:

https://www.sondermind.com/

https://www.nami.org/Home

https://www.inclusivetherapists.com/