This isn't a view you would assume most shark attack survivors would willingly sign up for. Mike Coots photo.

This isn't a view you would assume most shark attack survivors would willingly sign up for. Mike Coots photo.

When considering the things that might prevent someone from swimming into pounding Hawaiian surf, missing a limb would seem like a pretty reasonable deterrent. Similarly, when considering the things that might stop someone from pursuing a career in underwater photography–particularly underwater shark photography–missing said limb as the result of a shark attack also sounds like a sensible excuse to stay out of the water for the average person.

But then, Mike Coots isn't your average person.

The 38-year-old Kauai-born surf and wildlife photographer is an anomaly through-and-through. He's a photographer who ascended to the top ranks of surf photography despite not learning how to surf until after he lost his leg, and a man who took the whole mantra of "forgive and forget" to another level by dedicating his life to shark conservancy in spite of the fact that he became intimately acquainted with the working end of a tiger shark.

We at TGR were fascinated by Coots' story, so we got him on the horn to ask him how it all came together.

TGR: You're probably tired of retelling it, but run us through the shark attack that led to amputation.

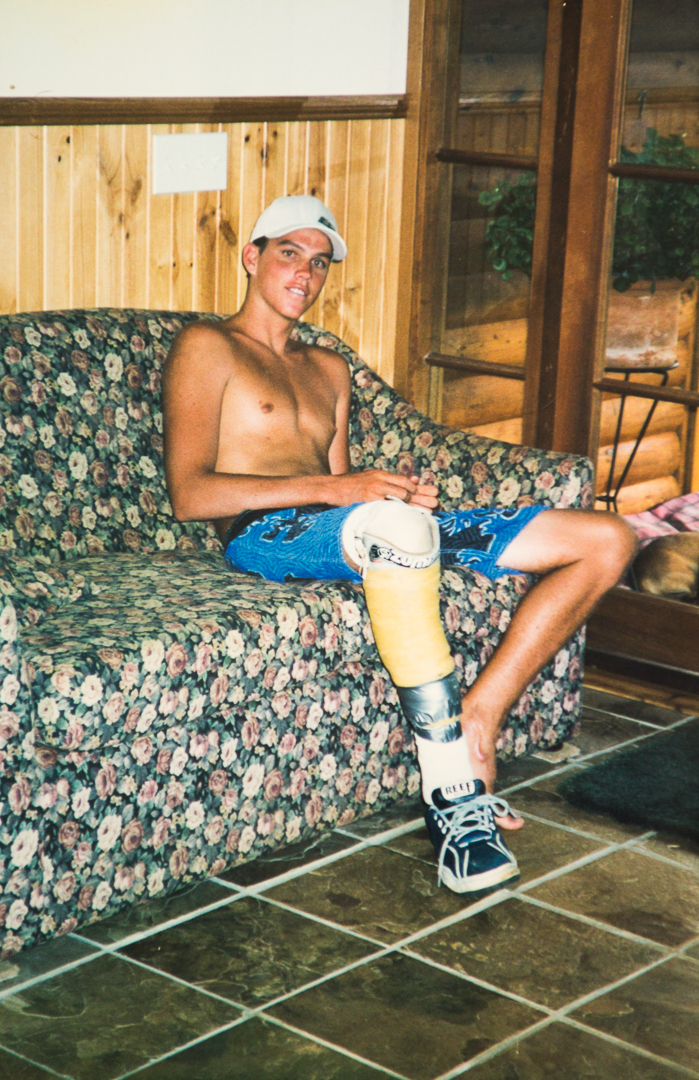

Mike Coots: No problem. I was 18 and had just graduated high school in June and was on a bodyboarding team called the Kauai Classic. I actually grew up bodyboarding and this was back in 1997 when you could still make a living off the sport, and I was hoping I would make it as a pro. I had a couple of guys I looked up to who were professionals, and I had a real shot at making it happen.

Then, the attack happened in late October right after I turned 18, and I became an amputee right there on the beach. It was a blindsided attack with no precursor. The shark looked like a submarine that came from below and started rag-dolling me. I gave it two or three solid punches, got back on my board and realized my finger was cut open, but had no idea my leg had been bitten off.

I looked over my shoulder and saw my leg was missing from my body, caught a wave to the sand, got a tourniquet and hauled ass to the hospital in the back of a truck. I had surgeries for about a week or so, they amputated my leg a few inches above the bite because of bacteria, I was bandaged up for a few weeks, the staples came out a month later and I was right back to bodyboarding at the same beach, but a bit further down from the attack.

You were saying you didn't even get into surfing until after the surgery?

MC: It sounds funny, but I hated surfing.

I had friends who were surfers but I was a diver and bodyboarder. One day, I was at school at the Brooks Institute for photography in Santa Barbara, [California], and it was this hot sunny day where me and all my friends were on the beach, and I wasn't going to bodyboard–all the breaks in Santa Barbara are these long dribbling point breaks. So I just decided to go surf.

It wasn't until he was in college–and missing his right leg–that coots picked up surfing. Mike Coots photo.

It wasn't until he was in college–and missing his right leg–that coots picked up surfing. Mike Coots photo.

At the time, I was told not to take my prosthetic in the water as it would void the warranty on it, and when you have a prosthetic, it really becomes part of your body, you get attached to it. It sounds stupid now, but at the time I thought it would break or bust or disintegrate if it got wet, and so there was a ton of trepidation before I paddled out–I mean, I imagined losing a limb again.

But it was maybe knee-high at the most, and we were drinking beers and a friend had a huge longboard, so I said, "Screw it, let's try it and see how it goes."

How hard was it to pick up the sport?

MC: When I was in college, I was really conscious about that prosthetic I was talking about. It was a bad length, it was constantly breaking, it had a rubber ball joint; it was super archaic. The quality of care for amputees in Hawaii is notoriously bad, and the prosthetics you find on the island aren't really meant for dynamic motions. So working with that old thing made it pretty difficult.

But after about a year of surfing with the ball joint ankle, I found there was a little screw on it I could get an Allen wrench on, and since I wasn't allowed to ask my prosthetist about taking it in the water since that would void the warranty, I just started tinkering with it.

I figured, if I could angle the prosthetic out, it would open up my stance more and make the riding feel a bit more natural. So when surfing, I angled it to what I called "toe out" and that was a big break through.

Now, through Instagram I got hooked up with this company in Iceland called Ossur and they're the world leaders in prosthetics: They make these carbon fiber feet they've been sending to me the past three years. The kinetic energy and return the carbon prosthetics give me from walking to surfing is on a whole other planet.

But for about four years in Santa Barbara, I was buying feet on eBay. I'd buy used prosthetic feet with different flexes for pennies on the dollar. Then I'd take a really sharp knife and cut toes off and experiment until I found the right fit. Nobody else was doing it and I could see immediate results with what I was doing. When I got it right it was like having that "magic board" surfers always talk about.

I did feel like Dr. Frankenstein occasionally. I remember one time I received twelve feet in a shipment from Germany all at once. Not too many people can say they once had a dozen feet shipped to them in the mail.

How much of a detriment was the injury to your surf photography career?

MC: In my college years my disability, if you’d call it that, was always in the back of my mind. I loved shooting from the water, but I feel like I'm dragging an ankle weight when I'm fighting those currents with the prosthetic on. It's like a newborn holding onto my ankle.

Coots no longer has to rely on his homemade prosthetic contraptions: He has all state-of-the-art equipment for surfing. Mike Coots photo.

Coots no longer has to rely on his homemade prosthetic contraptions: He has all state-of-the-art equipment for surfing. Mike Coots photo.

So, through college, I focused on increasing my photo editing skills. I knew it would be hard to swim in the water, especially shooting wide lens which requires me to be close to the impact zone, so I learned to shoot other types of photos. I found if I could use my brains, not brawn, to shoot then I could probably stay employed.

While I was learning it all, I was hired by Quiksilver to shoot their team in Hawaii for three months. I was stoked to work with them, because at the time they had the best team in the world. That said, I knew there would come a day when Pipe would crank and Kelly [Slater] or Mark [Healey] would be like, "Let's go shoot" that I couldn't fake it with an artsy angle and telephoto lenses. I was very afraid of big Pipe, but when the day came I just went for it. I was so nervous as I was walking to the beach with Mark that I didn't notice I put my wetsuit on backwards.

In my mind, I thought, "Maybe I can just stay on the shoulder of the wave with a long lens," and it ended up working pretty. It was good to see I could navigate it by using my brain instead of guts and balls and just trying to go into the pit and swim through it.

How much of your career would you say is now dedicated to surf photography?

MC: At present, I'd say only about five percent of my photography is surf work, the rest is portrait work and a lot of shark photography.

Why, after losing a leg to a shark, did you decide to get into shark photography?

MC: First and foremost because it's so dang fun shooting sharks.There's something about being underwater with a big predator and having a camera. It'd be one thing if you were spearfishing with a dead fish in your hand and all of a sudden you were face-to-face with a great white or a bull shark.

Coots gets up close and personal with a great white. Mike Coots photo.

Coots gets up close and personal with a great white. Mike Coots photo.

But, you give someone a camera, and it's a focus and a goal to achieve–getting the shot. Your mind gets off the fact you're in the water with the shark and it becomes a synergy with the big fish and you have a mission to document them.

Do you think that your standing as a survivor has benefitted your conservation activism?

MC: I think with social media, you now have this soapbox to share powerful imagery. And it's one thing to say, "I'm a survivor" but if you show really powerful imagery, I think that's what implores people to dig deeper on subjects. To get off their couch and shark dive for themselves.

I feel like right now I'm the luckiest person alive getting to do what I do. If I have a few more years of doing this I'd die a happy person.

__video_thumb.jpg)

Armel Tene

March 19th, 2018

Awesome bro nice adventure keep it up and well done also thank for this wonderful article.

Online Data Entry Services

sona khan

July 24th, 2019

click here For Kauai

click here For Kauai

click here For Kauai

click here For Kauai

sona khan

June 12th, 2020

https://2020calendrier.com/

https://2020calendrier.com/2020-calendrier-avec-semaine/

https://2020calendrier.com/calendrier-2020-canada/

https://2020calendrier.com/2020-excel-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/imprimable-2020-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/juillet-2020-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/aout-2020-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/limoges-scolaire-vacances-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/tunisie-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/2020-vacances-calendrier/

https://2020calendrier.com/calendrier-2020-musulman/

https://2020calendrier.com/calendrier-des-fetes-2020/

nice information

SKP Global

April 20th, 2021

Thanks for sharing such huge content keep posting further…. <a >Online Catalog Conversion services</a>